Hello, friends! 🌷 I’m writing to you from the sunshine of my front stoop, trying to squeeze all the pleasure I can out of this spring day after a week of darkness and gray. While I love holing up to write, I don’t love the feeling of having to choose between being in the world and sitting down to articulate my understanding of it. I’m grateful for moments when I get to do both. I’ve got my orange vanilla seltzer cracked, my skin is soaking up that Vitamin D, the birds are chirping all around, and the next installment of Open System is becoming.

As I start to get into a groove with this newsletter, I’m curious: What are you most excited to read about? Conceptual takes? Practical stuff? Personal stuff? All of the above? If you have any thoughts on that, or specific topics you’d like to see, let me know in the comments or send me a DM (@sti.mulation on the grammy gram)!

Speaking of things I discuss here, I’ve been reflecting lately on my relationship to my work as a sexual health creator/thinker. The nature of that work has evolved over time and I’ve taken breaks from it, but all in all, I’ve been at this for ten-ish years. Sometimes I’m excited by it. Other times I’m bored of it. But I do always believe that our cultural treatment of STIs needs to change and that, therefore, this kind of work is necessary. Still, I recognize that not talking about STIs on the internet is an option. I could just be quiet and go live my life in peace.

I had this moment the other night. I was getting into bed after drinking a whole half of a beer, and the guy who I most likely got herpes from popped into my head. I thought about how amicable and undramatic our entire romance/situation/whatever was. No stress, no wanting more than we had together — just two people enjoying the temporary intersection of our lives. It was a truly non-life-altering relationship (and I mean that affectionately)… except that I probably got a lifelong virus from it. And in a way, I’ve been writing about the aftermath of that hookup for 10 years. How random!

Of course, it’s never been about him or us specifically. When I’ve written about my experiences with herpes, I’ve barely mentioned the circumstances that led to my diagnosis, because it always seemed irrelevant. The point is: I got an STI, I realized how poorly society prepares us to deal with STIs and how stigmatized they are, and I wanted to fix that. But after zooming out in such a way that I could see how a casual situationship set in motion a decade-long body of work, that trajectory suddenly seemed so EXTRA.

In 2014, three years after my first outbreak, I conducted a series of interviews with former lovers to get their perspectives on herpes. I reached out to Mr. Undramatic, the last person I slept with before my diagnosis and the first person I slept with after, to see if he’d be willing to participate. He agreed. However, he also expressed that he thought I was making a “huge deal” out of herpes, because it’s “not that bad.” Though he was willing to do me the favor of answering my questions, he didn’t see the need for my project.

I remember reading his words and feeling misunderstood, and a little embarrassed. Here I thought I was contributing something to the world by opening up conversations about STIs, but what if the world saw my actions as mere catharsis, an oversharer’s attempt at healing? Healing implies brokenness, and I hated the idea of being seen as having let herpes break me. My diagnosis had prompted me to take newfound ownership of my sexuality, my desires, my entire self. I felt stronger than ever. But I interpreted his response to my work as an accusation of weakness. Whether or not that’s what he meant and whether or not he was right, I tasted the cringiness of that gap between how you think of yourself and how others think of you in my mouth.

In hindsight, I recognize that his dismissal may have been, at least in part, an attempt to distance himself from the distinct possibility that my herpes originated with him. Or maybe it came from an unacknowledged discomfort with his own status and how to navigate it in relationship. Incidentally, he never followed through with the interview. If he had, we might’ve unpacked his opinion and whether that had anything to do with why he only told me he had oral herpes after my fateful visit to the clinic, after he’d gone down on me. Alas!

Egos and personal dynamics aside, though, was I making too big of a deal about herpes? I agreed with the dude that the virus was “not that bad” — I’d said so myself in many a Tumblr post! Yet, I was giving it my attention. Lots of it. Don’t they say that giving something your attention gives it power?

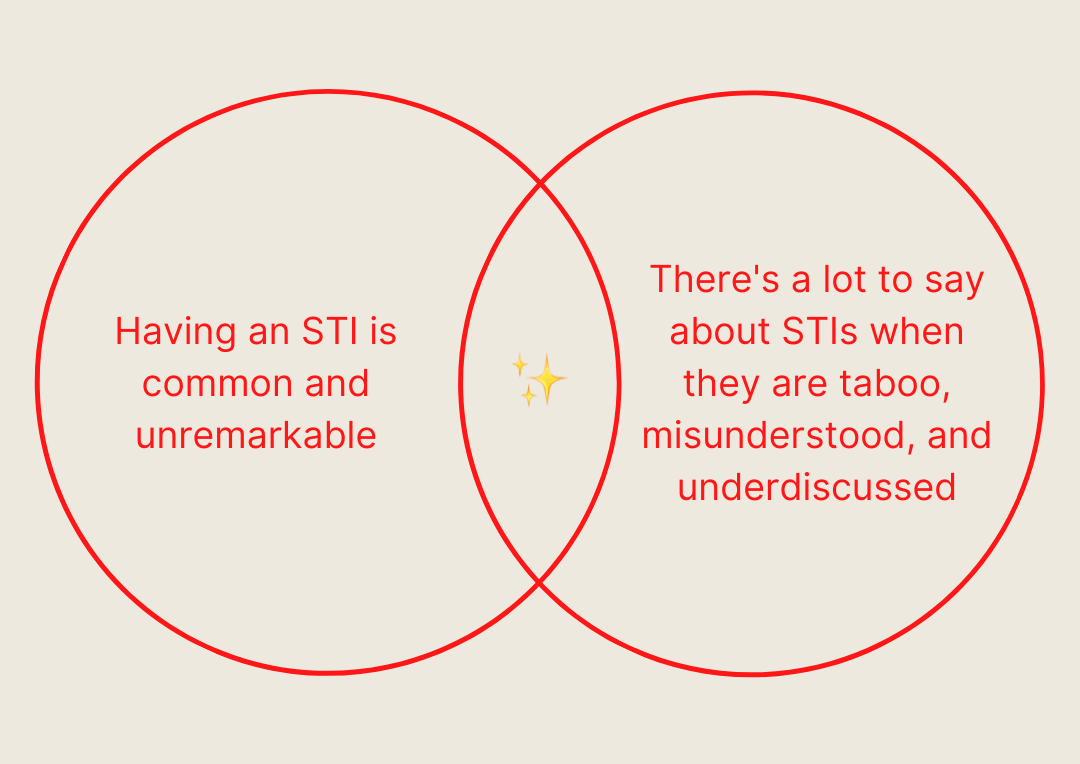

I’ve run into this argument periodically over the years: that an STI isn’t a big deal unless you let it be, and granting it your attention means you’re letting it control you. A step further, I’ve seen some people say that talking about STIs and the stigmas attached to them has an anti-normalizing effect by reinforcing notions of STIs as noteworthy or difficult to live with. (This logic isn’t exclusive to STIs; similar arguments get made about racism, sexism, anti-queerness, and more. Get over it, rise above, don’t be a victim, pull yourself up by your mental bootstraps.)

I do think we have some agency over our relationships to STIs. We can divest from and rewrite the narratives we’ve inherited, and as we do so, we start to change the fabric of reality. If I didn’t believe that, I wouldn’t be here! But here’s where I get suspicious. The idea that we disarm and cope with STIs by talking about them less? It strangely mirrors stigma itself by encouraging silence.

We already have more silence than we can handle. Lack of awareness and education around STIs is the norm, and our inability to discuss STIs openly leads to so much unnecessary confusion, hurt, and shame. I’m not convinced that more silence is the cure we need. (Granted, there can be such a thing as over-identifying with or obsessing over an STI, but that’s a conversation for another time. 🙃)

Maybe there’s a future in which STIs are so destigmatized and well-understood that there’s nothing to say about them anymore. But such a future requires a collective shift, and we can’t make a collective shift in silence and its byproduct, isolation.

My goal in writing about STIs has never been to resolve a personal issue so that I, personally, can move on. I have a stake in this, yes, but it’s bigger than me or a man I fucked in my 20s or any of us. Why did I cry when the nurse told me I had herpes? Why, despite knowing so little about the virus, did I initially assume it meant my sex life was over? Whatever I was reacting to, it wasn’t of my own invention. I had absorbed beliefs about STIs, without realizing it, that set me up for devastation. This is true for so many of us. THAT’S why I write about STIs. To understand how we got here and to map a way out.

One of the skills that I find useful on this quest: discernment. The ability to distinguish between, say, an observational statement (STIs aren’t a big deal) and an aspirational one (STIs shouldn’t be a big deal). Between an inherent reality (STIs aren’t intrinsically a big deal) and a situational one (STIs are felt and/or treated as a big deal within particular contexts). Between the biological expression of an infection and the social experience of it.

Over the weekend, I posed the question to my Instagram followers: What does it mean to you when someone says that herpes isn’t a big deal? The responses I received, some of which I’ve shared below, reflect the variety of meanings a statement can have.

Some people spoke to the physicality of the virus:

“not life threatening no major health repercussions”

“physically not dangerous, safe to have sex, transmission is low”

Others touched on emotional or social significance:

“That herpes (or any infection/illness) doesn’t define/affect your worth + innate wholeness!”

“an STI isn’t a personality trait”

“5-6 billion ppl on earth have it. Therefore, if you have it, it’s normal and not a big deal”

A few responses captured the nuances of context and subjectivity:

“Super dismissive. It SHOULDN’T be a big deal, but in real world it IS bc of stigma”

“It won’t affect your life that much and basically EvErYbOdY has it (I know 2 ppl who have it & suffer not a bit + 2 people who suffer GREATLY from it)”

Clearly, there are multiple interpretations of and answers to the question of whether or not herpes, or any other STI, is a big deal. Perhaps a more helpful way to frame this is: big deal according to what criteria? And as long as the answer is “yes,” then I think it’s worth talking about.